Knock, Knock, Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door - I

Writing the Perfect Email that Lands You an Internship

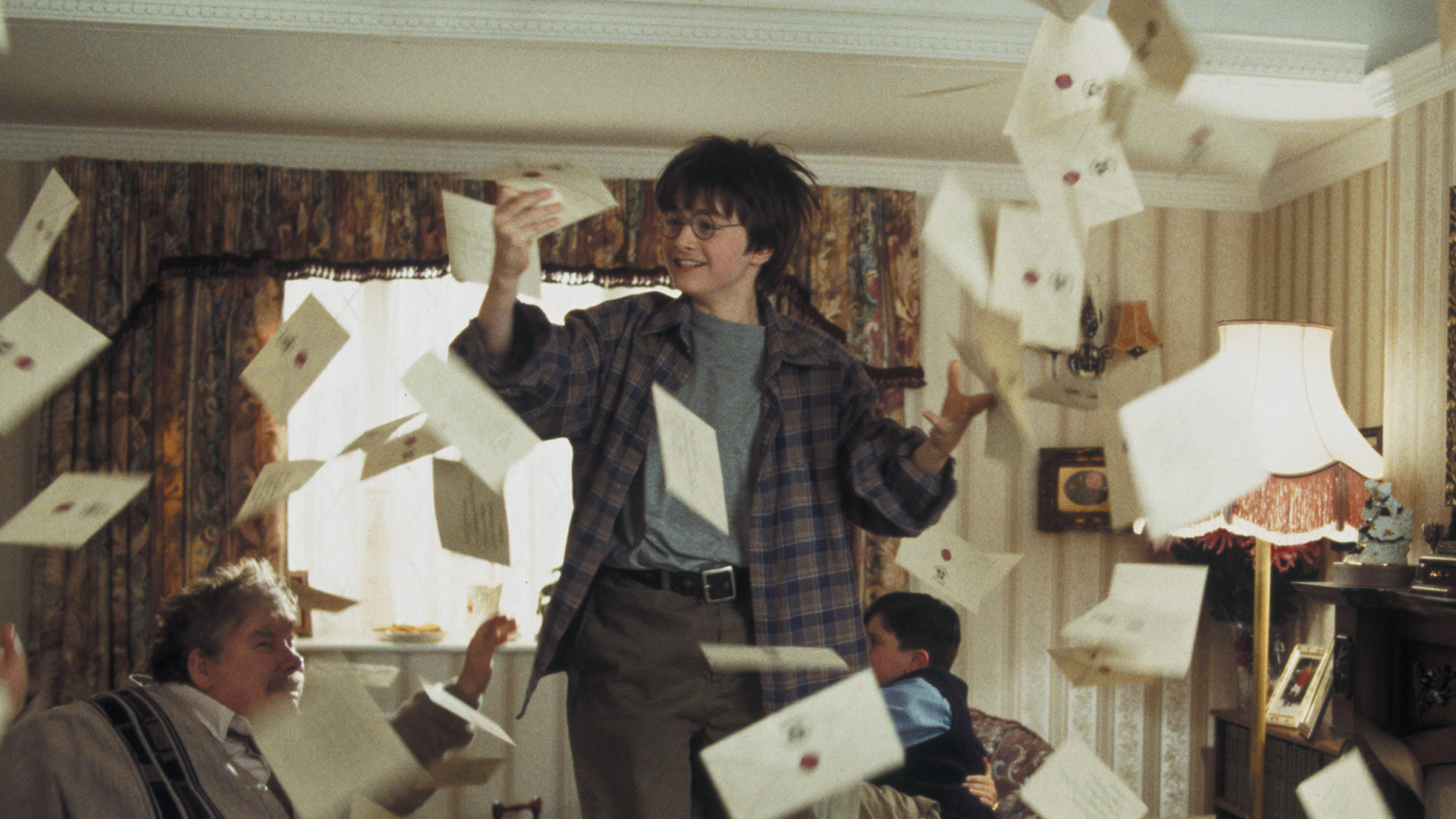

If you have ever applied for internships at academic institutions (particularly in the sciences) or are currently doing so, chances are that you have either sent your fair share of email to professors or are thinking of doing so. Writing emails to faculty professors is still one of the simplest ways of getting internships. This means that professors get a large number of such emails throughout the year. To stand out from this crowd, one needs to adopt a specific and well-thought-out strategy. There is indeed no shortage of such blog posts all over the internet. Nevertheless, we thought we should chip in with our experience and ideas regarding writing emails to prospective mentors.

We have divided this post into two parts. In the first part, we will discuss the important points that must be mentioned in an email. It will be a broad overview of these points. In the second part, which will come as a separate post, we will take up a specific email as an example and discuss the different details of this email. Although this post is aimed mainly at undergraduate students, postgraduates and researchers can also benefit from the general pointers. At times, you might find this post too elaborate for summer internships or short-term projects. We will quote William Blake in our defense - ‘You never know what is enough unless you know what is more than enough.’

Prologue: Set the stage

Establish context: Mention the topic on which you want to work.

Students are generally not interested in particular topics in their undergraduate days, so it’s okay to have a broad spectrum and choose a general topic such as high energy physics or cosmology. Before writing to a professor, you should make sure that your interest overlaps with theirs. It also shows that you have done your research about your potential mentor. It is a good measure of your interest and enthusiasm, and those count as essential qualities in a research student.

Justify the topic: Explain why you want to work on it

After choosing a topic, you have to explain your reasons for doing so. Here you have an opportunity to be original and stand out. Just explain in your own words why you find this topic interesting. Describe how you came to love this topic - maybe you studied it and immediately fell in love with it, perhaps you gradually realized the depth, elegance, or power of the topic, or possibly there are some very cool applications that you read about somewhere. Keep it honest and simple. Grand gestures are not required and are, in fact, discouraged. To see what happens if one uses fancy jargon like ‘black hole thermodynamics’ or ‘ QCD’ just for the sake of them, check this link. That sort of practice looks pretentious and will make your prospective mentor lose interest.

Story: Take your shot

Describe your background: How well are you equipped for the project?

Now you have to connect your chosen topic with your background. That background might involve any lectures or workshops you have participated in. An example would clarify what we mean. One of the authors (Suvranil) was once selected for an internship on ultrafast optics. At that time, he knew absolutely nothing about that topic. The project, however, required knowledge of mainly perturbation theory and specific numerical methods, most of which he had already studied during their undergraduate years. The upshot is that it is not necessary to know powerful techniques and take advanced courses to participate in a project and make meaningful contributions to it. Make sure to carefully read through the professor’s recent projects from their website and google scholar profile. Try to understand which skills might be helpful. At the end of the day, all that matters to your mentor is whether you can get their job done. (While the last sentence is mostly true, there are exceptions.)

Connect your interests with those of the professor: Why does their work appeal to you?

This is probably the most challenging part. Your job here is to say why you are interested in the professor’s work. Try to stay as objective and specific as possible and avoid making generic flattering statements like “Your research is really novel and state of the art!” or “You are the international leader in this field…”, and the like. Before writing to the professor, check some of their publications and talk about the parts of the papers that you find either interesting or thought-provoking. Make sure to give an honest account of why you found them fascinating. If you have any genuine comments on the publication(s), include them as well.

Reading a paper is tough, especially if it’s your first time reading one. We do not generally recommend reading the paper in full detail on the first attempt, especially before sending the first email to the professor, because it will take a lot of time. It’s best to tackle it in various stages (see this article for a more elaborate discussion). Start by reading some of the introduction. Once you get a brief idea of the goals and context of the work, try going through the results and discussions. If you feel you can still continue, read the section on the methodology. Reading the methodology is quite daunting. You should start by studying the images and graphs to gain an intuitive understanding of the mathematical content. If you still haven’t had enough, you can try working out the calculations yourself.

Epilogue: Smoothly land your shot

Bring up your future goals: How does this internship help in that direction?

You should write a few sentences about your future goals and how this experience can affect those goals. Having certain clear plans for the future demonstrates your intent and determination. These goals can be as simple as learning a new method or as meticulous as planning for your doctoral research. Try to choose your project supervisor and topic in accordance with these goals so that you have a clear motivation in mind.

Some Parting Advice

Keep it short!

Our final suggestion is to keep the email simple and honest. A short, to-the-point email shows your professionalism and respect for the reader’s time. You should keep in mind that many professors will offer to take project students simply so that the students can get some exposure. Make sure to make it easier for them by staying concise and relevant. Try to stay as grammatically correct as you can - mistakes will only make it harder for them to read your email.

No reply? Never Mind!

After doing your best, you will often end up getting negative replies or no replies at all (well, no reply is also a reply!). If you do not receive any reply within a week, send them a gentle reminder and wait for one more week. If you still do not receive any response, move on. The correct approach is to list a number of professors you want to write to for internships and then keep sending emails according to this list. So you should start the whole process at least 3-4 months in advance of your internship time frame.

Other Resources

We found some very good articles on writing emails for internships. Interested readers are strongly encouraged to read these articles for more hints and to learn professors’ perspectives about receiving emails.

-

How to write an email/application for a short-term or summer research internship/project? - This is our go-to place for any academic email writing tips.

-

Dear Potential Post Doc or PhD Student - top10 ways to get a position in my lab - This one is a mind-blowing satirical note. We really recommend reading this, especially after a long, tiring day.

-

Dear Dr. Neufeld - While this article is mostly for students applying for a Ph.D. program, some tips are pretty general and work for any case.

-

How To Write Emails Asking for Research Internships - Template, Strategy, and Resources for Undergrads: Please read point number 2 of this article; we found it really insightful.

-

Tips for Applying to a Summer Research Program: This is another resource for making sure you have ticked all the boxes before sending your email.

Comments